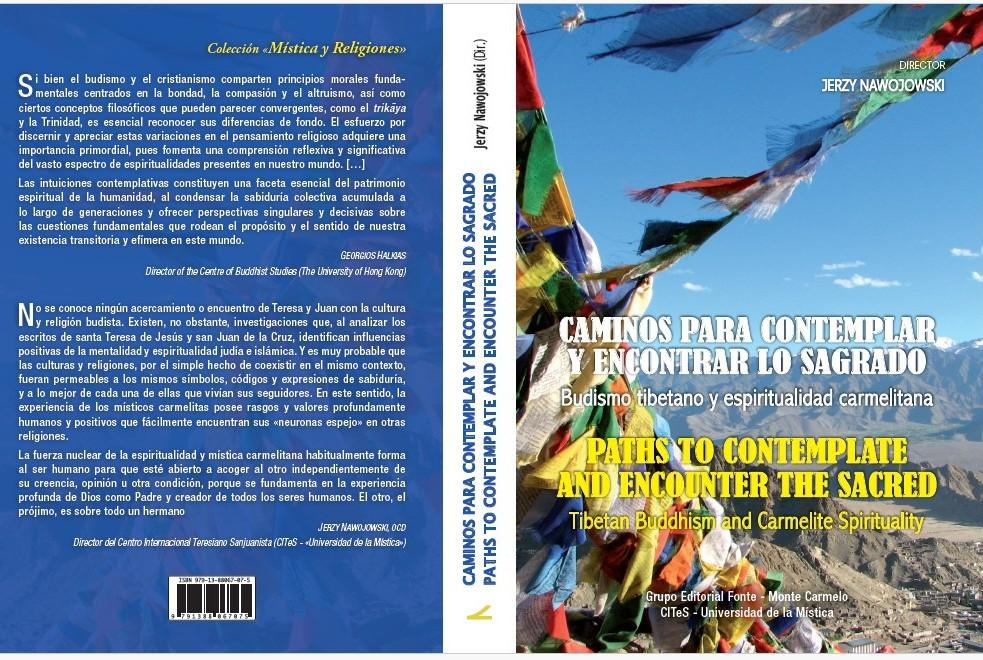

Paths to contemplate and find the sacred. Tibetan Buddhism and Carmelite Spirituality/Paths to Contemplate and Encounter the Sacred. Tibetan Buddhism and Carmelite Spirituality, directed by Jerzy Nawojowski, OCD, and published in 2025 by CITES, “University of Mysticism”, and the Fonte—Monte Carmelo Editorial Group, is a living memory of the “Third World Teresian Mystical Encounter and Interreligious Dialogue”, held in Avila from July 25 to 28, 2024. This origin is key to understanding the volume: it explains and justifies the diversity of records it collects and its intention to preserve and transmit not only academic content, but also a concrete experience of interreligious coexistence.

At the organizational level, the book reflects the solid collaboration between the various institutions that structured the congress. The meeting was convened and co-organized by the Order of the Discalced Carmelites, the Teresian-Sanjuanista International Center (CITES) of Avila and the Center of Buddhist Studies (CBS) of the University of Hong Kong (HKU), with the collaboration of the Dharma-Gaia Foundation (FDG), which acted as the promoter and co-organizer of the event. This congress represents the third fruit of this collaboration.

The volume also represents the consolidation of an ambitious project in spiritual terms, initiated in 2016, when CITES and what is today the FDG conceived of building a sustained bridge that would connect Carmelite spirituality and Buddhist traditions. The tour began in 2017 with a meeting dedicated to primitive Buddhism and the Theravāda tradition, continued in 2020 with a conference on Chan/Zen Buddhism and Christian mysticism —interrupted by the pandemic, but documented in editorial format— and culminated in the 2024 congress focused on Tibetan Buddhism. In that sense, this volume does not constitute an isolated gesture, but rather a visible stage in this systematic interreligious dialogue.

The volume documents an encounter designed as a bilingual and hybrid space, where theoretical reflection coexisted harmoniously with practical workshops, rituals and recitations. Under the title “Guidelines for visualizing, contemplating and finding the sacred”, the conference shifted the focus from mere doctrinal exposition to the phenomenology of practice, exploring the role of the body, image and silence in the transformation of consciousness.

From a perspective of academic rigor, it is crucial to have partners with specialized competence, because their intervention allows us to sustain the dialogue beyond the exchange of impressions and to frame it in a conceptually demanding comparison. In this regard, CBS and CITES provide a solid framework in Buddhist and Christian traditions, respectively. In turn, the FDG plays a key mediating role: it translates this work into guidelines that can be incorporated into the daily lives of practitioners.

The title of the meeting precisely defines its approach: it does not propose a duel of doctrines or a forced synthesis, but rather a shared exploration through practicable “paths” —ethics, discipline, contemplation, rituality and discernment of experience—. This methodological option is especially relevant both for Tibetan Buddhism, with its repertoire of visualizations and ritual media, and for the Carmelite tradition, with its cartography of internality and its pedagogy of prayerful silence. This turn—moving from the comparison of statements to attention to practices and their fruits—explains much of the volume's interest for specialists and practitioners, and allows dialogue to move from the purely intellectual to the construction of shared itineraries.

The volume is organized in four parts: (1) framework of interreligious dialogue; (2) paths of Tibetan Buddhism; (3) paths of Teresian Carmel; and (4) comparative studies. The sequence is clear and didactic: first it introduces essential concepts and vocabulary; then it lets each tradition speak in its own terms; and, finally, it proposes a comparative reading between the two. In this review, however, we chose to follow the order of the conference program, which presented in parallel the itineraries of Tibetan Buddhism and Carmelite spirituality. This “mirror” journey makes it possible to progressively contrast similarities and differences in key aspects—such as ethics, attention training, contemplation and the culmination of the path—and reproduces with greater fidelity the dynamics of dialogue as developed during the meeting.

Conceptual Framework for Interfaith Dialogue

The opening ceremony of the congress, held on July 25, 2024, established from the beginning the importance of interreligious dialogue between Christianity and Buddhism. In this first session, both Dr. Jerzy Nawojowski, OCD, director of CITES, and Dr. Georgios T. Halkias, director of the Center for Buddhist Studies at the University of Hong Kong, presented the Carmelite and Buddhist perspectives, respectively, laying the foundations for the meeting.

Professor Georgios Halkias opens the volume with the proposal to shift attention to interreligious dialogue: instead of seeking doctrinal correspondence, it is more profitable to work in comparable fields in which traditions can be found: ethics, attention development, rituality, contemplative practices and narratives of holiness. Dialogue is thus revealed as a place of understanding between religious traditions and as an instance for reviewing one's own spirituality. It is not a question of attenuating differences, but of maintaining them rigorously, avoiding both syncretism and unproductive exclusivism.

Accordingly, Father Jerzy Nawojowski argues in his introduction that, in an increasingly technified world, personal encounters are diminishing and interreligious dialogue is presented to us as a necessity for our human and spiritual growth. It anchors this openness to the other in essential aspects of Carmelite spirituality: prayer, inner purification, detachment, charity. The conference is presented as a space for working together in meditation, contemplation and in experiencing the sacred.

Mutual presentations

Caverio Cannistrà, OCD —former founder of the Discalced Carmelites and professor of theology—, in his paper “The Order of Barefoot Carmel and the Teresian mystique”, provides a perspective born from his experience of residence in a Japanese Shingon monastery, which enriches the dialogue from an experiential dimension. It presents the Teresian reform as a path whose dynamism springs from the encounter with the fallen Christ, and carefully distinguishes between human effort and contemplation understood as a free gift, oriented to a transformative union. For Cannistrà, mystical authenticity is verified by its concrete fruits—humility, compassion and community life—signs of a more loving humanity, and thus shows how dialogue can deepen one's own tradition without diluting its roots.

The Dr. Phuntsok Wangchuk, honorary professor at CBS (HKU), examines in his presentation “The Foundation, the Way and the Fruit in Tibetan Buddhism” a doctrinal framework on spiritual evolution in Tibetan Buddhism. The “base” is the innate and pure buddhadic nature of every being, even if it is obscured by ignorance; the “path” is the sequence of transformative practices necessary to update that potentiality and free oneself from suffering. Finally, the “fruit” symbolizes the highest sphere of enlightenment or Buddha state, where mental poisons are eradicated. These pillars are interdependent: the foundation of the practice, the path is the means and the fruit is the final recognition of the primal essence.

Morality and Discipline

The sister Maria Jose Perez, OCD, a nun from the monastery of Puzol, presents us in her paper “To push hard on virtues, but not on rigor” the Teresian asceticism of Friendship, that is, the development of Teresian mysticism towards an inner work. The author highlights how Teresa turns her attention away from the outside world to the limitless exercise of virtues such as fraternal love, forgiveness, renunciation and humility. This “asceticism of Friendship” is a distinctive mark in her Carmelite spirituality: holiness is not found in physical rigor, but in a cordial surrender that makes her come to Christ and to the maximum personal openness to him.

Dra. Catherine Hardie, professor at CBS (HKU), in her paper “Tibetan Buddhist Perspectives on Discipline and Morality”, explains that the ethics of Tibetan Buddhism is based on Bodhicitta, an altruistic aspiration towards enlightenment to liberate all beings. This tradition organizes its principles into three vehicles (śrāvakayāna, mahāyāna and vajrayāna), each with hierarchical commitments (Pratimoksha, Bodhisattva and secret mantra). Although vajrayāna is considered superior, the vows must be observed together. Ethical norms vary depending on the vehicle: śrāvakayāna promotes avoiding negative actions, mahāyāna uses “skilful means” to benefit others, and vajrayāna transcends conventional moral distinctions, while externally respecting traditional codes.

Pre-contemplative experience

In the chapter entitled “The Precontemplative Experience”, Dr. Juan Antonio Marcos Rodríguez, OCD, deputy director of CITES and professor at the Comillas Pontifical University in Madrid, addresses the spiritual dimension prior to contemplation. The author retrieves for analysis the term ”Acquired contemplation”, a concept that is echoed in the first systematic articulation of the Carmelite tradition. Beyond this historical context, the analysis is mainly based on the work of Saint John of the Cross to identify the instrumental and pedagogical elements that define this spiritual stage. Especially valuable is his analysis of practical mechanisms and reflection on nuclear categories and metaphors —the wound, the center, loving care—that illuminate this development from a perspective that articulates theory and practice in the field of Carmelite mysticism.

The Dr. Klaus-Dieter Mathes, professor at CBS, in his paper “Meditation on deity in the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism”, explores how deities in Tantric Buddhism (Devatās) are manifestations that emerge spontaneously from the enlightenment of the Buddhas in correspondence with the needs of the disciples. The author details that, under the guidance of a tantric teacher, the practitioner must first discover and identify with the divine form most suitable for realizing his inner Buddha. This “divinity to be appreciated” (Isthadevata) becomes the way in which one conceptually visualizes oneself during the creation stage, a process that facilitates the overcoming of attachment to the ego and other harmful dualistic mental states. Mathes stresses the importance of understanding that this self-image as a deity is similar to a rainbow, devoid of inherent existence, an understanding that leads to a non-conceptual realization of the true nature of the mind.

Mystical Visions

Dr. Pedro Fraile Yecora, professor of Biblical Greek and Sacred Scriptures at the Regional Center for Theological Studies of Aragon, in his paper “Mystical visions and the encounter. Carmelite perspective”, explores the Carmelite mystical tradition since the mystery of the Incarnation as a hermeneutical key. The writer analyzes the positive evaluation of bodily reality by Sacred Scripture and comments on various texts by Teresa of Jesus and John of the Cross, where he highlights how, despite the dualistic mentality prevailing in the 16th century that considered the body as an impediment, both mystics overcome these limitations to build, based on their experience, a doctrine of spiritual life in which the bodily dimension is not annulled, but rather integrated and transformed. For Teresa, the encounter with the Risen Christ reveals the value of the glorified body; and for John, the person, in his incarnated reality, is configured as a place of divine manifestation.

Mystical experiences in Tibetan Buddhism are interpreted from an epistemology focused on the understanding of the mind and emptiness, as he explains Georgios Halkias in his paper “Mystical Visions and Encounter. Tibetan Buddhist Perspective”. The author proposes a classification of these experiences into four main categories: encounters with enlightened beings, visions of pure lands, experiences of mental luminosity and experiences of direct transcendence. In his analysis, Halkias examines specific phenomena such as “terma” (revealed treasures) and contemplative practices such as dark retreats and “sky-gazing”. Discernment is essential to avoid attachment to visions or ego inflation, stressing that these experiences, while valuable, must function as skilful means to deepen understanding and cultivate wisdom on the path to awakening.

The ultimate goal

In “The Supreme Goal or Union with God. From the perspective of Jesus Christ and Christian mystics”, FCO Javier Sancho Fermin reflect on the various ways in which the ultimate goal of the Christian is named in Catholic terms, whether it be happiness, heaven, holiness, salvation, the Kingdom of God or union with God. He says that none of them can cover their entirety. In its interpretation, “salvation” stands out as the key word of the evangelical message not only in an ethical and eschatological sense but also as “salus”: liberation from everything that constricts human fullness, pain, attachments or selfishness. Following the experience of Jesus and Christian mystics, he affirms that this ultimate goal is aimed at harmony of being, personal integration and a universal loving commitment.

In “Updating the Sacred Ultimate in Buddhist Mysticism”, Khenpo Yeshi explores the concept of realizing the supreme goal in Tibetan Buddhist mysticism based on texts from the early Tibetan traditions of Chan (“Zen”) and Dzogchen (“Great Perfection”). These texts are of particular interest because they speak from the perspective of the ultimate objective, using the language of a path that requires no effort. In this way, the work provides a comprehensive examination of the theories and practices involved in achieving enlightenment within Tibetan Buddhism. Starting with a review of Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and the idea of no-self or emptiness, we will consider the three Buddha bodies (kāyas) and how the Buddhas act in the world. The core of the matter is the question of whether the ultimate goal of Buddhahood consists of a simple cessation of appearances and activities, or whether it continues to manifest and act in the world for the benefit of suffering beings.

You can read the second part of this review here